by Jody Harrow

standing on the shoulders of those who came before us

In any professional pursuit: financial, manufacturing, food prep or the arts (including music, acting, art, dance and design) there is a wealth of information to garner from people who came before us. It is their gift to us that we can look up to them for inspiration. Because my training is in art, design and craft, they are the voice from which I speak. But I truly believe what I present here can be applied to any platform you might be engaged in.

within a continuum - not a vacuum

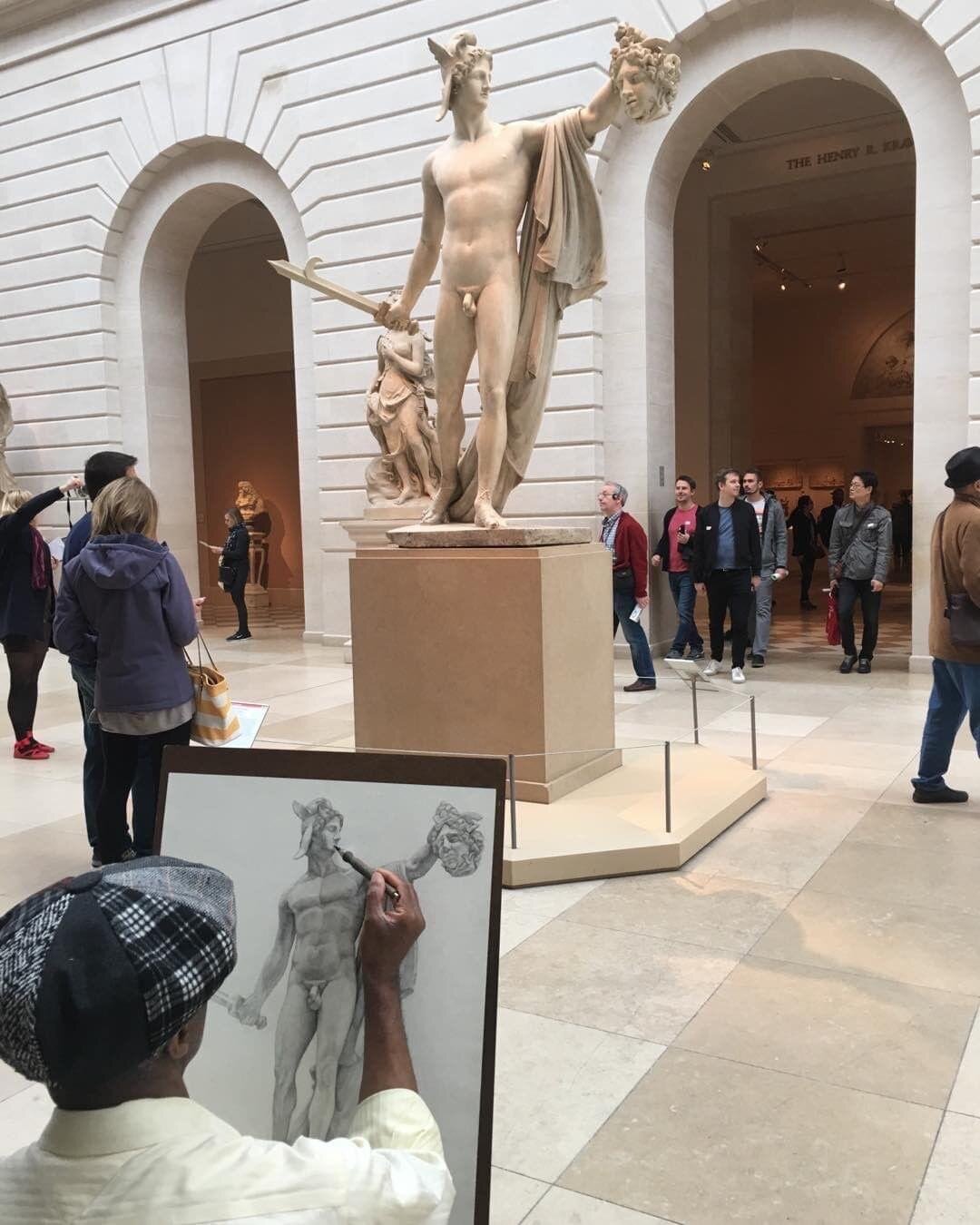

I have spent countless hours and 40+ years exploring the origins art, sculpture, textiles, lighting and, jewelry to enhance and possibly take to the next level to innovate with my hands-on skills the process of making. Absorbing the origins links us to the past artists/makers to integrate their craft and eye so we can bring something new and exciting into the present. We then provide a platform for someone in the future to look at our work and grow from.

How do we dive deep into the rich history of knowledge left behind? In the visual arts it can come from taking in museum exhibits and gallery visits. If this is not physically possible as at present due to limitations of access or our Covid restraints, absorbing visual material garnered from photographs and writings is virtually at our fingertips.

a schism was formed

Starting in the 50’s an intentional turning away from and forsaking the study of the historical precedent in art, design and craft has led to a break of that continuity. Honoring our past was seen as wrong to teach in art schools and universities. Instead we went all in for the physicality of painting which then morphed into eye candy. For example, simply crumpling a piece of wire and then handing it to foundry resulted in a sculpture several times its original size. For the ‘artist’ this would then become a priceless sculpture meriting a place at the entryway of a New York skyscraper.

Due to this lack of substance in art, I’ve noticed a recent trend in which artists turn to verbiage to give a sense of weightiness to their work - candidly talking about the basis of their work with the recognition and understanding they’ve received from it and on and on. Personally I see this carrying little weight and it seems more like a disconnect to the work itself - a stand in and shoring up of an artwork that is devoid of meaning.

While studying at the Brooklyn Museum School during the mid-70s, I witnessed the dismantling of their looms due to a lack of interest. The times were changing economically: woven mills had moved to the South from New England and would soon be taken off shore - hello opioid pandemic!

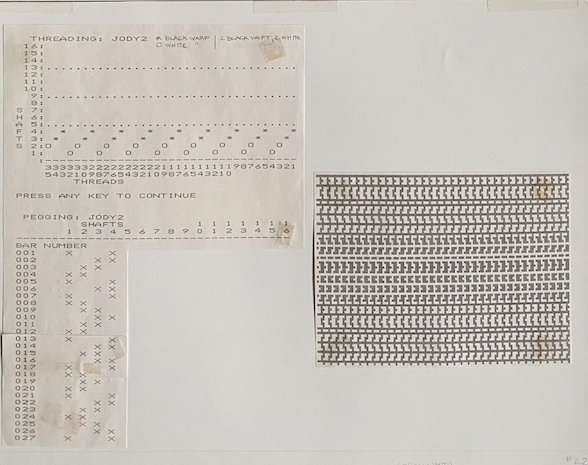

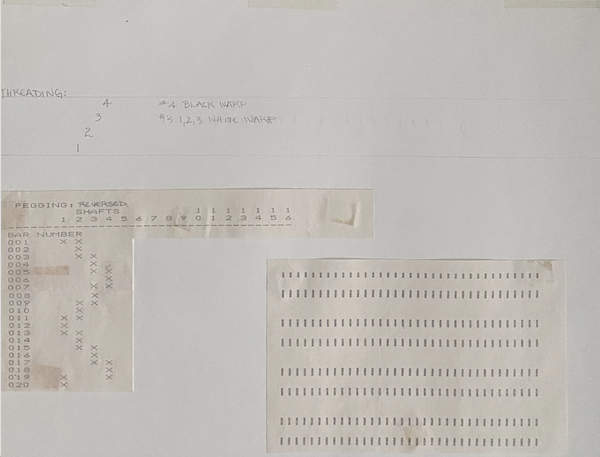

Again, when I taught at Parsons School of Design in the early 2000’s I witnessed them dismantling and carting away vestiges of a textile department that students used for many years to be forsaken and replaced with a computer. I’d taken a computer generated weaving class in Berkeley CA in 1982 where Steve Jobs donated his Apple II computers for our class with the intention of trying to attract an audience for his personal computer. I could see both the limits of the loom as well as the computer and the efficacy of the marriage of the two. Ironically, computer coding has it’s origins in the loom. This innovation started in the early 1700’s in France and culminated with the Jacquard loom a century later when punchcards were used to automate the weaving of complicated damask patterns.

In the process of obliterating precedent and moving manufacturing to other parts of the world for less costly labor, we have all but wiped out this very important hands-on craft and a certain gratification from handwork that comes from the making. But for the odd student pursuing on their own, we are faced with a weak and possibly irreparable link. We can no longer be the conduit to integrate our past to the future. Not only do I see this paradigm play out for the artist but for the museum curator, collector and the intermediaries selling the artist’s work to the collector.

It has gotten to the point where ‘those in the know’ purport that Art, Design and Craft are separate entities, and never the twain shall met. But recently the scale has begun to tip toward forming a bridge between these disciplines - Design + Art as well as Craft + Art. The marriage of art and design seems to be making incremental inroads when as recently as last year’s Armory Show decided to include some design-like (functional) art pieces into its show. 😮

Presently there is a Whitney Museum show titled Making Knowing: Craft in Art. This is so exciting because when we marry the making of our materials and our tools for crafting with a knowledge of precedent that innovation can come about in Art, Sculpture, Furniture or Wearable Art. Only when we place ourselves in the middle of this continuum may we be humbled by the process - a process that allows us to integrate pieces of the puzzle to bring into being the next new, awesome art, craft or design piece.

they ran with it and presently other museums are taking their lead

This is why I was adamant in a paper presented to the Cooper Hewitt Museum that they connect their collectiosn from the past with those from the present when forming an exhibit. For example, what came to my mind was the bicycle. They are in this unique position as an institution to be both in possession of the historical and the contemporary. Because of the breadth of their collection they were the one museum that could pull this off. And now my daughter and I have noticed the world of museums have caught on - borrowing from other collections to enhance their exhibits.

Museums can go even further by engaging their community and developing a communication with them by posing questions to their audience based upon their needs and desires and then becoming a place for that exchange. They can then take the communication to the next step by integrating aspects of that engagement into their exhibitions. Whereas privately funded museums are not relying on community, they instead turn to their curators and donors to choose artists from their collection to make a statement - talking at people instead of with them. David van der Leer, a curator interested in transforming traditional exhibits, eloquently relays the message of museums developing with a community and not for a community.

I remember well when interviewing James Turrell in 1982 and discussing his site-specific work, he mentioned museums being archaic institutions and likening them to mausoleums. While they have to some degree attempted to integrate with their audience since that time, they still have a long way to go.

artist’s shout became a scream

Toshiyuki Kıta - lighting

In Western culture the “me“ sits at the center of everyone’s universe whereas in Asian cultures they possess a rich history that sets the precedent in which the “me” becomes subsumed by the “we”. In 2007 Toshiyuki Kita, a contemporary lighting and furniture designer based in Japan had a show called the future of tradition. He says, “In the present era where globalization proceeds at a rapid pace...it is essential for us to contemplate on what is our cultural heritage, traditional culture.”

Mr. Kita also made the distinction between art and design saying, “The basis of design is communication, so it is for people. Art is for oneself.”

where is our historical footing?

Without having an historical footing in our works, both through process and intellectually, Western Art, for the most part, does not seem to know how to modulate its tone. Oftentimes we are left with a high screech that begs, ‘look at me, look at me!’

Malevich @MoMA 2017

Jackson Pollock

The precedent for this has it’s origin in a cold war battle that the CIA waged and projected onto our culture in an attempt to prove we could outdo the Soviet Union in art. After an early 20C renaissance in abstract art known as Constructivism, the Soviet Union turned it’s back on abstraction and Stalin mandated only realism in Art in the mid-century. Enlisting Rockefeller wealth to incubate this plan and as a way to mask its origins from their stable of left leaning American artists, the CIA went all in to promote them. Thus Modern Art was born in America.

You might ask, “Where does Graffiti fit in?” I see it as a great art form that comes from the basic need of a people to fulfill their calling to express themselves. Graffiti artists are part of the American population who would otherwise be barred from an out-of-reach academia elitist community that has the luxury to make art for resale. Outsider Art as well fits into this category.

Henry Darger - Outsider Art

There are some artists and designer who can navigate in the modern art world well integrated with craft and design, but it takes a certain amount of introspection and understanding of these aspects of making which I touched upon. A few of these artists/designers that straddle this universe are the Campaña Bros (the Jenette Chair is named after a collector who has generously supported both their and my design endeavors). I recently discovered a kindred spirit in Dawn McNutt, and Kiff Slemmons is in a league of her own with a body of jewels that perfectly marries art, craft and design, as well as cheeky wit.

Only when institutions of learning for both children and adults can scale a seemingly insurmountable wall to impart a rich historical knowledge as well as teach the repetitive slowness of a trade and craft, will we once again be able to gain a footing into making and thinking with both weight and substance.